Hello everyone

Here is Part 1: Chapter 2 of my new book. Every time I read this chapter I think there is something not quite right in it, but I’ve rewritten it so many times I’ve decided to leave it alone.

See what you think and leave comments or email me with positive and negative feedback - both are very welcome.

Till next chapter

Maree

CHAPTER TWO: WORLDVIEWS AND ASUMPTIONS

Defining Worldviews

Worldviews frame the way we make sense of the world. They represent our beliefs, values, and assumptions about what matters, what we define as ‘real’ and what is not, what we accept as ‘right’ and what we reject. Koltko-Rivera (2004) gives us a detailed definition:

A worldview is a way of describing the universe and life within it, both in terms of what is and what ought to be. A given worldview is a set of beliefs that includes limiting statements and assumptions regarding what exists and what does not (either in actuality, or in principle), what objects or experiences are good or bad, and what objectives, behaviors, and relationships are desirable or undesirable …Worldviews include assumptions that may be unproven, and even unprovable, but these assumptions are superordinate, in that they provide the epistemic and ontological foundations for other beliefs within a belief system.

Worldviews have tacit, limiting statements and assumptions that are superordinate – they shape not only our present; they also shape what we believe will or will not emerge in our futures. And since these assumptions influence our knowledge systems and what we believe to be real or not, they are powerful influencers on our thinking and the actions we take.

If you research ‘worldviews’ though, you will get a wide range of definitions and categorisations of what a worldview is and its scope – personal, local, national, global – all of which are influenced by the worldviews of researchers and their fields of interest.[1] Some research focuses on defining frameworks) for how a worldview develops, which is what I am writing about here - a couple of interesting ones are:

§ Emilia de la Sienra, Exploring the hidden power of worldviews : a new learning framework to advance the transformative agenda of education for sustainable development, a PhD Thesis which developed a Transdisciplinary Framework on Worldviews and Behaviours, linking neurology, mind, mental states, decision making, and behaviours; and

§ David Rousseau and Julie Billingham, A Systematic Framework for Exploring Worldviews and Its Generalization as a Multi-Purpose Inquiry Framework. This is a detailed exploration and definition of the components of a worldview.

Be prepared: a bit of theory follows.

Constructing Worldviews

In my PhD research, I discovered a framework developed by Clement Vidal (2008, 2014) which provides one way to define how worldviews are constructed, and how its components can be identified. Vidal drew philosophy in this work and suggested that while the term ‘worldview’ is frequently used without being defined clearly, everyone needs a worldview to make sense of our world:

Most people adopt and follow a worldview without thinking much about it. Their worldview remains implicit. They intuitively have a representation of the world … And this is enough to get by. But some curious, reflexive, critical, thinking, or philosophical minds wake up and start to question their worldview. They aspire to make it explicit. Articulating one’s worldview explicitly is an extremely difficult task (2008, p. 7).

I’ll pause here because this quote for me might be at the core of why we accept or reject futures. The evolution from unconscious to curious minds and from worldview limitations to critical thinking about futures is incremental over time, so a single futures process will not immediately ‘find’ foresight. It requires a mental leap of faith to move beyond what we know we know in the present to becoming curious and willing to challenge our assumptions about the usefulness of that knowledge in our present.

We reject some futures as impossible because we hold implicit, unchallenged assumptions that generate the closed minds and strong assumption walls. We know when we hit that wall because we will always have some sort of reaction at some point, emotional or visceral, which indicates you are dealing with something that is challenging your deeply held assumptions. Without ways to understand this reaction and move beyond constrained worldviews and assumptions, our minds remain closed to the new in the present, and our worldviews are never articulated in their entirety. In my experience as a consultant this has sadly become the norm in most processes, simply because it is indeed quite difficult for us to question our worldviews and staying in our comfort zones is easier than imagining new futures.

Vidal suggests that overt worldview construction is difficult because it is emerges from our cultures where collective meanings are developed, embedded, and transmitted. Our worldviews ultimately emerge from both our inner and outer experiences, as well as from the impact of history and scientific developments. It is the inner experience that I write about here. Now for the theory.

Vidal’s Framework

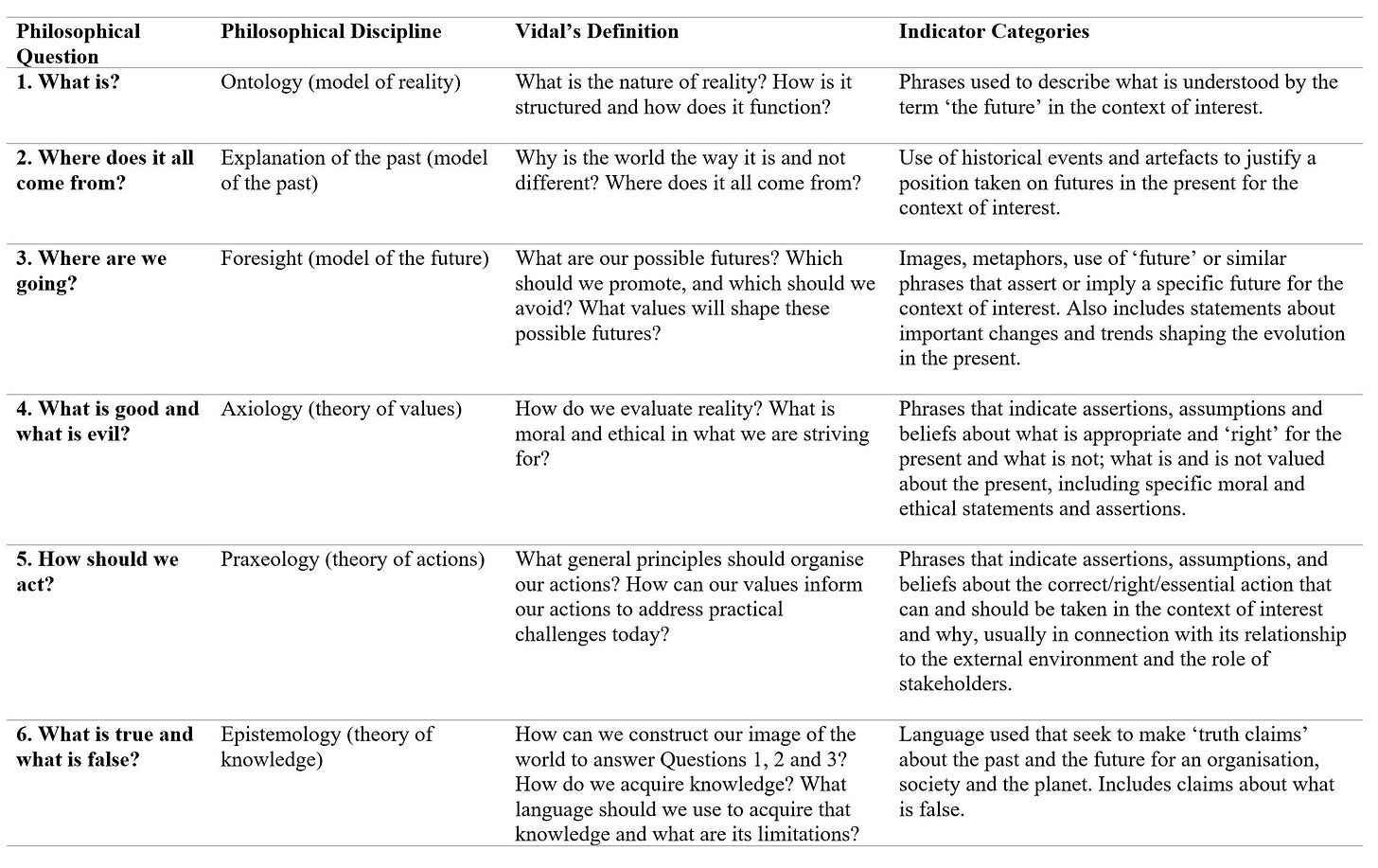

Vidal’s worldview construction process is grounded in six philosophical dimensions – descriptive, normative, practical, critical, dialectical, and synthetic – that he divides into first, second, and third order knowledge and that are, in turn, understood by answering seven ‘enduring’ questions derived from the ‘big questions’ of philosophy.

Table 1 summarises Vidal’s components of worldview construction – both questions and the philosophical area from which the questions are defined. The words used are a little ‘academic’ which they are, but I believe the point is clear enough.

Table 1 Vidal’s Worldview Construction Frame

First order questions are those that “directly question our world and how to interact with it”. Answering them articulates our values and assumptions about our realities.

Second order questions “are about the origin of our answers to those first-order questions” and inform second order analysis. Why did we answer first-order-questions as we did? And how can we talk about these questions and answers and accept them without judgement? Answering these questions can tell us what knowledge we accept as valid and what we believe to be true.

This set of questions brings me back to that quote from Carl Jung that I used in the preface: thinking is hard, that’s why we judge. Imagining new futures is hard work, and that’s why our unconscious assumptions let us judge some images as acceptable, and we reject others – rather than being a futures image worth considering. Our assumptions and reliance of ‘the future’ make it easy and more comfortable to judge these images as valid or not.

Vidal writes that achieving synthesis at the third order level is a difficult, if not impossible, task and reminds us that each level can be explored separately. Importantly though, he writes: “What is dangerous and ridiculous is for a philosopher to claim that one of the dimensions is the only real or true way of philosophizing” (Vidal 2014, p. 8). I suggest this applies equally to how we think about and imagine futures. No imagined future is true or false because we have no futures facts, and there are always multiple futures to explore in the present – because there are multiple worldviews that shape those futures.

What Vidal’s worldview framework provides is an approach that can help us begin to understand the nature of our worldviews that influence our thinking about and imagining new futures. Let’s explore that a bit more.

A Futures Worldview

I adapted Vidals’s seven questions for the FS context where we can ask them individually and collectively to surface our assumptions.

Question 1: Ontology - What is? This question asks us to define what how we understand our realties in the present. Do you believe reality is what you can empirically observe and measure? Or do you accept that our reality involves more than what we see - that our individual and collective interpretations of it results in multiple worldviews about reality? Answers here also condition our acceptance or rejection of our futures – if we believe that our images of one future is right and matches our assumptions, we will reject most others.

Question 2: Past: Where does it all come from? This question asks us to reflect on our past and present and their influence on our present. Why is the world the way it is, and not different? Are there global organising principles? What trends[2] from the past have shaped our present? What are my/our existing narratives that we use now to inform our we create our futures imaginaries in the present? Our interpretation our pasts co-exist with our presents influence the emergence of our futures images.

Question 3: Futures: Where are we going? Answering this question surfaces the images of ‘the future’ that we hold in our minds and that become usually only when we are called on to articulate them in some way. When we can surface our assumptions and challenge them we can imagine our futures in more expansive and deeper ways in the present. Then we can reframe how we understand change, omnipresent trends and global shifts and find new actions in the present.

Question 4: Values: What is good and what is evil? The assumptions that underpin beliefs about ‘the future’ are shaped by our values, whether espoused or unconscious. Which alternative futures should we promote, and which one should we avoid? How do we live a good life so the conditions of life for people in our futures are positive? How can we organise a good society now and in coming years? How do we evaluate global reality? How can we strive to ensure inclusive, sustainable futures for everyone?

Question 5: Actions: How should we act? These are the actions that flow from our values and beliefs about reality, the past, present and ‘the future’. What are the general principles that we should use to organise our actions to achieve the most sustainable outcomes? Answers here lead to more inclusive approaches and plans of action, informed by our values, to address critical issues in the present.

Question 6: Epistemology: What is true and what is false? Responses here relate to what knowledge we accept as valid and are at the core of contested assumptions about the present and futures. What we accept as valid knowledge also helps to explain why some futures are accepted and others are rejected.

Question 7: How do we begin to answer the previous questions? This is the question this book is exploring by defining and mapping the assumptions we use as one way to better understand the impact of our worldviews on our thinking about and imagining our futures (Part 2). The aim is for us to recognise that we need to let go the futures that we think we can manage and achieve by identifying and challenging the assumptions that construct and embed that thinking.

Rather than dismissing clashing opinions of others or telling them they are wrong, we can accept that perspectives are not universal; they vary across different individuals and groups. Equally though they may not necessarily be valid or useful when applied to a wider, more collective context where many worldviews will intersect, collide, and be challenged. The point here is to be able to accept there are many perspectives on any issue, different ways of knowing, and all need to be recognised and considered before they are rejected – and to know exactly why you are rejecting them. A quick example.

Synthesis: This space is where a new way to have conversations about the present and futures can emerge when clashing worldviews about futures intersect in positive ways. It is the coalescence – or synthesis – of individual and diverse worldviews in those conversations that can enable an expanded collective interpretation about what new futures may emerge over time and leave behind the assumed, right, only future. The question that drives this synthesis is: can we reframe our individual understandings of the present to begin to integrate the most positive and useful aspects of multiple worldviews about our futures to enable new thinking and new perspectives to emerge?

Worldview Indicators

The worldview questions are one step but how do we identify them in our language, interactions and artifacts? One approach I developed in my PhD research to make the four clashing worldviews in universities more overt was to identify worldview indicators in a set of ninety-one existing scenarios about university futures. By reading and analysing the scenario narratives it was possible to categorise them as emerging from one of the four worldviews and showed that these futures co-existed today. I did this categorisation by using some indicators to interpret the narratives – these indicators can also be found in tangible artefacts and images about futures to allow us to make our worldviews more explicit. What are these indicators?

Worldview indicators are images, metaphors, descriptions, terms, phrases, assertions, constructions and other artifacts that enable the components of taken-for-granted assumptions about futures to be identified and articulated.

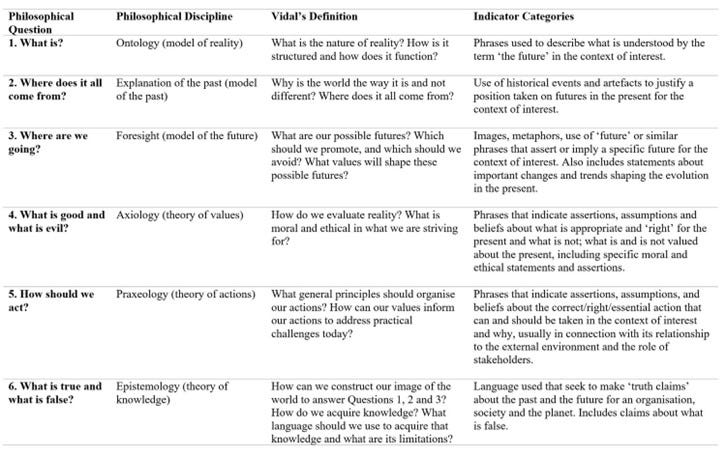

Table 2 adapts Vidal’s worldview questions and definitions with suggested worldview indicator categories and questions to identify those indicators in a FS context. Answers to the seventh question – where do we start to answer the previous questions? are emergent in the shared, interpretive, critical conversations that become ‘real’ in our futures processes – and so are not included in the table. More about that in Part 3.

Table 2: Worldview Indicators

Questions 1 to 5 in Table 2 are Vidal’s first-order questions - they ask us to become aware of our individual and collective worldviews that influence our thinking our futures. The answers to these questions inform how we answer Question 6, a second order question which is about how we acquire and use knowledge about our imagined futures (that is, our context of interest), and can only be answered after we explore the first five questions.

Questions 1, 2 and 3 are descriptive in nature. The answers describe what we are thinking about futures and the assumptions we are using. Question 4 in a normative question that asks us to define our individual and collective values in the present since they are likely to shape the futures that we can imagine and use in the present. Question 5 is a practical question, one that focuses on action to be taken today. Question 6 is a question that asks us to critique and expand our ways of finding and interpreting knowledge that we use when we are imagining futures.

We will explore how to use these questions in practice in Part 3.

Opening up our worldviews to surface all futures that can be known is essential in the present. We should be seeking not to dismiss futures held by others but to value them as starting points to create the divergent space we must explore in the present. In this space we dismiss nothing at first and accept the need to use different ways of knowing about futures. Critically, how we receive and either accept or reject information or images of our futures depends on our worldviews which, in turn, inform our actions. And worldviews are difficult to challenge until the individual is open to doing that.

[1] This is why I made it clear in Chapter 1 that is my worldview shaping the text of this book, based on my epistemic and ontological foundations.

[2]Trends are important as a starting point in FS. They represent the present in a single context usually, and while we do need to understand the complexity of our external context, our interpretations of those trends are often frighteningly similar once you take them out of the context in which they were developed. Instead, changes that are identified at the system level first and cross multiple contexts I like, isolated in an industry, not so much, because the result is constrained thinking and little possibility of finding the new and novel.

Hi Maree- I'm keen to offer feedback but I thought it wise to read Chapter 1 first. Is it available?